US based "Car Life" actually said "Probably 80% of the billions of miles of passenger-car driving in the U.S. every year could be driven more effectively and more enjoyably in one of these cars." For an ego boosting review, get reading.

FOR AN IMPORTER to bring three cars of 99-inch wheelbase and 4-5 passenger capacity into the U.S. just before the introduction of Detroit's new "compact" cars is a bold stroke-little David slinging the first stone before the Michigan Goliath raises the club.

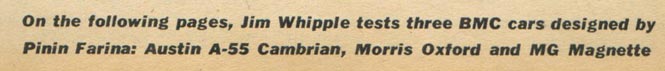

The three new English cars, Austin's A-55 Cambrian, the Morris Oxford and the MG Magnette Mark III, are from separate divisions of the British Motor Corporation, a manufacturing complex that could be termed accurately as the General Motors of England.

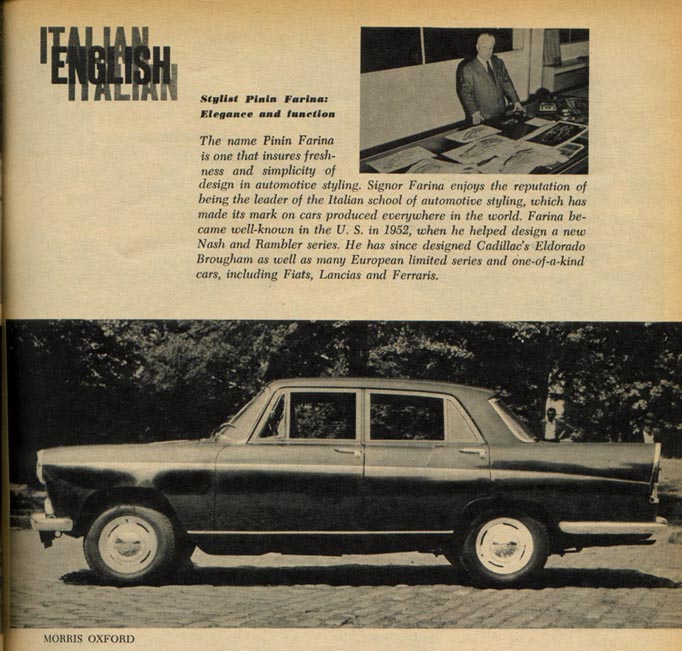

The Morris Oxford is the big brother of the familiar and fabulous little Morris 1000. Oxford is a familiar car name in England but this is the first model to be brought to the U.S. in volume.

MG's Magnette III is a brand-new version of a car that has been familiar to U.S. car lovers as a sleek sedan with some sports car characteristics.

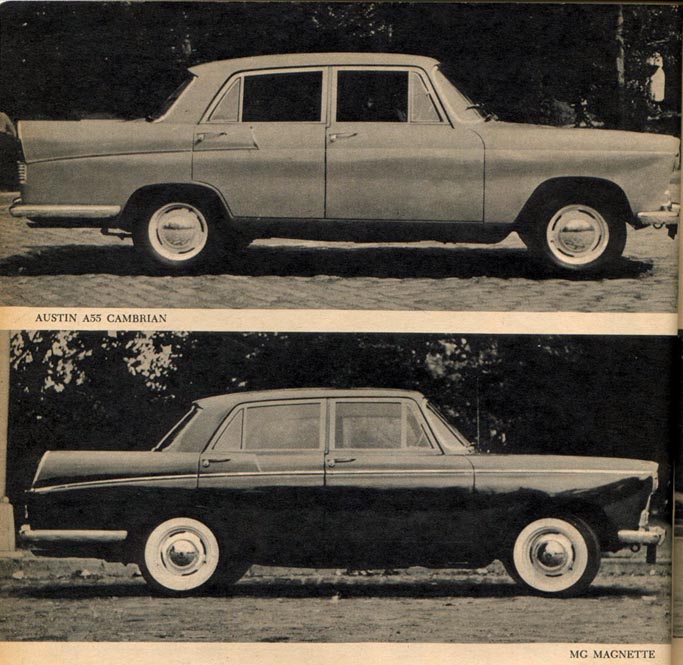

Credit for their crisp good looks goes to Italy's outstanding automotive designer, Pinin Farina of Turin.

Signor Farina is a stalwart exponent of the school of design which maintains that it is neither necessary nor desirable to disguise a four-door sedan as a supersonic missile with juke box overtones.

Perhaps the greatest measure of Farina's talent lies in the natural, uncontrived look of his designs, all of which make the adaptation of metal and glass into containers for passengers, luggage and power plant look both easy and correct. And this, especially on cars that are generous in some dimensions yet compact in others, is no mean feat.

The easiest way to make a car look fast, sleek and powerful is to give it a low, wide body structure. Width should exceed height, and the entire car must be close to the ground. In order to add the low look-and for structural reasons-American cars in recent years have been made wider than the demands of ample seating space decree, so that today we see U.S. cars 80 inches wide yet only 55 or 56 inches high. The Farina-designed BMC cars with their height of 59 inches and width of 63 tend to look tall and narrow in comparison with our domestic road-straddlers.

However, I found that the more time that I spent with these cars the better I liked their looks. With ever passing day I come to appreciate Farina's light, deft touches; the sloping lines of the windshield, crisp contours of the roods, the model "glass house look" of the stainless trimmed windows, the sleek, uncluttered, down-curving hooks and rear decks, the well-balanced lines of the side paneling.

I even came to accept the fins as the most tasteful examples of their kind, although I couldn't help wondering how well the three cars would look with a simple, tapered fender line.

One thing is sure however. The factory two-tone paint jobs don't improve the overall appearance of the new bodies. Color separation between the top and bottom includes the fins and the top of the rear deck along with the roof paneling color, usually dark, while the hood and balance of the side paneling and lower trunk lid are contrasting or complimentary color, usually light.

The two colors on the rear quarter panel areas break up the flowing lines of the cars, giving them a "busy" look and making them appear smaller than they actually are. A happy exception is the Morris Oxford where the color division follows the natural and attractive line between the roof panel and the body proper.

Maybe it's only a coincidence, but the early batch of BMC "Farinas" brought in by the East Coast distributor-Hambro Automotive Group-have been single color paint jobs. The colors themselves are all very attractive, especially a rich, dark British green, and a maroon appearing on the Morris Oxford.

Inside these packages, it seems that Britons do not feel it's necessary to provide room for more than four large adults. However, an occasional fifth passenger car be accommodated in any of the three cars.

Rear compartment in each is actually 55 inches wide, which on the face of it makes the rear seat a three-passenger proposition. However, there is a "rub". The rear cushion and back are sharply curved over the front corners of the wheel arches. As a result the "outside" passengers of the trio tend to sit at uncomfortable angles and slide towards the center of the cushion.

Up front, it's plain that BMC designers don't intend even occasional three-passenger use. In spite of the 52-inch width of the compartment, on the split bench seats in the Austin, single bench of the Morris and individual semi-bucket seats of the Magnette, there just isn't enough room for three. To clinch matters, all three cars are equipped with floor-mounted shift levers. (Austin A-55 Cambrian may be ordered with column remote gearshift control.) So, for all practical purposes of travel, the BMC "Farinas" are four-passenger cars.

However, those four passengers get the most comfortable accommodation for cars of this size and weight. There's excellent leg room for driver and front passenger. There's plenty of space for feet in the deep-dish foot wells that are recessed under the front seats.

Now is a good time to explain that in spite of some considerable differences in character, appearance, equipment and prices, these three cars share the same body and chassis. So, to a great extent general comments about styling design and dimensions apply across the board. All share the same four-door bodyshell and frame on the same 99 ½-inch wheelbase.

Treads are identical at 48 7/8 inches and 49 7/8 inches front and rear. Weights run from 2287 (dry) fro the A-55 to 2464 (dry) for the Magnette-not a huge difference. Rear axles, drive lines, transmissions, clutches, brakes and front suspensions are also basically identical. All three cars share the same 1489-cubic-centimeter (90 cubic inch) displacement, four-cylinder engine, which is already familiar to MGA fans.

The overhead-valve power plant is rated at 53 brake horse power on the A-55 and at 55 bhp on the Morris Oxford. In both cases there is a single SU inclined carburetor. As installed with twin carbs in the Magnette, BMC's well-proven four turns out 66.5 horsepower at 5200 rpm compared to 4350 rpm for the maximum reading on the two other cars.

Along with the more powerful version of the engine, the Magnette has a higher rear-axle gear ratio of 4.3 to 1 on the A-55 and Oxford. Although this doesn't sound like a great difference on paper, it's really noticeable out on the road where it brings in the Magnette's greatest power at higher speeds.

For example, the limit in third gear of the four-speed transmission on A-55 and Oxford is just about 60 mph on the level with the single-carb 55-horsepower engine, while the 66 horsepower Magnette winds up to 70 mph.

The lower (4.5) ratio has on advantage. It enables drivers of the A-55 and the Oxford to start in second gear on level roads when lightly laden. The fact that second (as well as third and fourth) is a fully synchronized speed makes traffic driving just that much earier on all three cars because you can flick the gear lever down into second when you're crawling at five mph without a murmur and get a powerful thrust that will take you right up to 40 on the A-55 and Oxford and 45 on the Magnette.

Third gear is useful for passing at road speeds especially in the 35 to 55 mph brackets although the lower rated versions of the engine are just about at peak of their power curves at 55 in third.

Frankly, I would try to get the Magnette's 4.3 ratio with the Morris Oxford's 55 horsepower single carburetor engine, and forego the Oxford's second-gear starts in favor of a little higher acceleration limit in third gear and a quieter and more economical top cruising speed for turnpikes in fourth gear.

At 60 mph on a high-speed super-highway, the A-55 and Oxford are just about at their optimum comfortable cruising speed. They can be cruised at 68 to 70 without strain, but the overall level of fan and exhaust noise becomes a little tiring. Top speed on the "smaller" engined models is a bit over 75 mph.

The deep-breathing, twin-carb Magnette with it higher ratio cruises effortlessly at 65 to 70 with engine roar not coming on 'til you're above 70 mph. Flat out, the higher-powered Magnette will touch an honest 85 mph. At this speed the noise level is unpleasant and the susceptibility to cross winds makes steering a little touchy.

Acceleration of the three cars was a happy surprise. Both the Austin A-55 and the Oxford will show pickup from 50 or 55mph on a moderate grade and top the rise at 65. The Magnette will give you a gentle shove in the back at 60 on an upgrade when you floor it and reach 70 or better in a couple hundred yards.

This isn't sensational performance compared to the big V-8's of 200-plus horsepower, but whenever I floored the accelerator of the Magnette, I could keep right alongside U.S. six-cylinder sedans in high-speed, uphill acceleration.

In short, the performance of the BMC "Farinas" is more than adequate when they're lightly loaded, with the Magnette standing about 15% higher than the A-55 and Morris Oxford. With normal loading-four adults and four suitcases-any one of the trio will take any long-distance run at legal speed limits very nicely. But if cruising at 80 is a requirement in your motoring, these Englishmen will not be your dish of tea.

For a mixed bag of city driving, cross-country hacking on narrow roads and turnpike cruising at 60 or 65, there cars have few equals. Probably 80% of the billions of miles of passenger-car driving in the U.S. every year could be driven more effectively and enjoyably in one of these cars.

First of all, the new BMC cars are delightfully easy to drive. Their steering is light and accurate. At three turns lock to lock-the same on all three-it's just right. Not too quick and sensitive, but "faster" than on all but a few U.S. cars. There's no power steering, of course, for the very logical reason that it isn't necessary even in parking maneuvers.

It should be mentioned at this point that the new cam-and-lever steering is not as precise and direct as the rack-and-pinion of the older Mark II Magnette. The steering wheel is large and mounted at a comfortable angle; however, its rim may interfere with the direct over-the-hood vision of shorter-than-average drivers.

The four-speed transmission with its floor-mounted control is the same on used in the MGA sports car and is one of the most enjoyable features of the entire control setup. Naturally the higher seating positions of the three sedans makes a longer lever necessary. However, the greater leverage resulting makes shifting lighter without any loss of precision in the shift pattern. The synchromesh operates smoothly and allows very fast shifting.

The pendant-pedal hydraulically-operated clutch will let you engage the drive slowly and gently or will bite crisply on a high-speed shift. Combined with the smooth, direct-acting gearshift the BMC clutch helps you to get the maximum potential from the engine's displacement.

Transmission gear ratios are nicely spaced for smooth, continuous acceleration. Indirect gearing is not dead silent, but neither is it annoying even when pressed near the limit in each range.

The brakes on these three cars deserve special praise. They are smooth and quiet in action and require very little pedal pressure. The reason, in addition to good design, is the extremely generous lining area of 146 square inches. Comparison with an American car like the '59 Oldsmobile with has 191 square inches of lining area and weighs almost twice as much as the A-55, will give you an idea of just how ample these brakes are.

They work so easily that I compare them favorably with U.S. power brakes, which give you the feeling that you could slam a car into a panic stop with just your big toe.

All three BMC cars handle nicely, but none-and this included the Magnette-approximates a sports car road-ability. The Magnette has somewhat firmer action in shock absorbers and consequently a bit less roll in the cornering, but like its two "juniors" it isn't set up for drifting and powering through corners.

As a matter of fact in all three there is a moderate amount of understeer at medium speeds, but when pressed to the limit the rear will shake loose and provoke an oversteer condition. Maybe the fair amount of body roll is intended to discourage drivers who like to play "sports car" and drive these cars immoderately.

I couldn't help but wondering why, at least on the Magnette with its emblem of sporting tradition, BMC engineers didn't install a torsion anti-roll bar. This would tend to make the car feel more sporting when taking sharp bends within the limits of safe speeds and beef up the safety margin for those who may occasionally run along the ragged edge.

Riding qualities are excellent on all three cars and are surpassed by only two or three cars of comparable weight and wheelbase on either side of the Atlantic. The suspension is utterly conventional but well-balanced; coil springs front, semi-elliptic leaf at rear, with double acting arm and lever shock absorbers all around.

Aside from the distinctive looks of their grilles and tail-light-fender assemblies-and of course, nameplates-the greatest differences among the three lie in the arrangement and treatment of their interiors.

The A-55 is the least elegant of the three, having no built-in clock, only one front-seat ash tray and a two-spoke steering wheel without the horn ring. However, the Austin is by no means austere.

Cushions and seat backs are genuine leather, rear compartment is carpeted, there are twin sun visors, twin windshield wipers and rear seat armrests. In addition there is crash padding on the upper instrument panel and on the edge of the parcel shelf.

Upholstery backing is foam rubber over springs on the seat cushions with hair padding over the springs on the backs. Front seat cushions have a projecting roll at their forward edge which supports the drivers thighs and makes for a high level of total seating comfort. I prefer the firmer cushioning found on the Oxford and the Magnette which I thought was more comfortable that the A-55's seats, cushioned in the ultra-soft U.S. tradition.

Instruments on the A-55 are excellent; twin dials with white-on-black lettering and good indirect lighting are visible directing in front of the driver. One is a very readable speedometer complete with trip odometer, white the other contains a fuel gauge, and oil pressure gauge as well as an ignition warning light. Switches are conveniently located and crisp in action.

A general impression of the A-55's interior is that it contains everything necessary for comfort and convenience and that workmanship is careful and meticulous. My one complaint in comparing the A-55 with its two sister cars concerns the sound surpressing job which is average for a small, unit-construction car on the A-55 but definitely better on the Morris and Magnette.

The Morris Oxford's interior differs from the A-55's in that there is carpeting in the front compartment (with rubber mats at high wear points), a bench-type front seat, arm rests in the front seat and the firmer cushioning mentioned earlier. The instrument panel has a wider raised and cowled area, different location of the ignition key, a clock, two-tone paint and instrument dials with trim and color with make them less legible than the A-55's.

The Oxford's firmer cushioning and superior soundproofing, plus the lateral support of the center armrests (front and rear), in my mind justifies the additional $61 over the price of the A-55.

The Magnette, costing $426 more than the Oxford (price included $55 heater defroster which is an extra on the A-55 and Oxford), offers luxury and horsepower as the inducement for shelling out the extra bucks.

Mechanically it differs in the dual-carburetor engine with its 11.5 additional horsepower, the higher rear axle ratios and firmer-acting shock absorbers. The interior is an all-out effort toward medium-priced luxury with a sporting flavor.

In my mind the most important advantages are the contoured semi-bucket front seats which really give some lateral support, and the cowled raised instrument grouping which comes close to perfection from a readability standpoint.

The instrument lighting is novel and effective. It is governed by a three-position switch which first snaps "on" to illuminate all instruments with indirect green light. The alternate "on" position send a special "black light" just to the speedometer needle and numerals so that the radio light glows like a watch dial.

This permits constant visibility of the speedometer and permits the driver to snap on the other lights for occasional check of fuel level or engine temperature. U.S. designers could do a lot worse than to copy this system, which has only one flaw-the designers couldn't resist chrome plate for the molding around the glass face of the instrument cluster. This bit of trim feeds back some glare from the full lighting.

Heater and defrosters are the same on all three cars except that the control knobs are of different materials. The heater will cram in a high volume of air without the use of the blower at 40 to 50 mph.

Trunk space is identical on all three of these new cars and is far more than you would expect. There's 19 cubic feet of space, all in one square useable chunk unencumbered by spare tire, structural members, counterbalance springs or intruding fuel filler pipes. The trunk lid opens right from the floor, which is directly at bumper level so that you can load from an easy 20-inch lift from the ground.

The spare tire is ingeniously located in a sturdy metal pan, closed against most of the elements, which is located beneath the trunk floor. To reach the spare for that once-every-two-years flat tire, you simply insert the wheel wrench handle into a socket in the trunk floor and crank until the hinged pan lowers and permits you to slide the tire directly to the ground. This can be done with a minimum of disturbance to the contents of the trunk.

Incidentally, the square shape of the trunk enables you to cram it full with a multitude of odd-shaped items without resorting to jigsaw puzzle tactics.

All three cars have an interesting door latch feature which American auto makers would do well to imitate as soon as possible. On all rear doors a small switch located on each latch body can be moved to automatically lock the inside door handle, thus making it impossible to open the doors from the inside. At the same time this feature allows the rear doors to be opened from the outside. In addition there is the conventional locking feature-which comes into play at the other position of the concealed switch-permitting either opening or locking from the inside by the conventional handle.

What this means to families with small active children doesn't have to be spelled out. I appreciate the typically British procedure of including this device on all models at no extra cost, which is a great way to win friends and influence prospects.

The riding qualities are much better than I've come to expect after year of trying out imported cars and finding the best that could be said for them ride characteristics was that they were "tautly controlled." These new BMC cars are all of that, but in addition they're downright comfortable and compare very favorably with the U.S. "compact cars" of under 110-inch wheelbase. Only on winding, bumpy and high crowned roads did I wish for lower center of gravity, wider tread, and more anti-roll control.

These cars have faults, but they're minor ones, such as the mild distortion in the extreme corners of the windshield, poorly located window regulators and interior door handles, less than effective sun visors, and a front seat regulator on the Oxford that snags trousers and skirts.

The chief obstacle to really big sales of these cars is the U.S. market is that from a price standpoint all three of the face some pretty tough competition, both imported and domestic.

Nevertheless, the solidly-built, attractive Farinas have a great deal on the ball and nobody on the market for a family car in the $1900 to $2800 bracket should buy without a thorough investigation of BMC's trio. END

Editor's note:

Cambridge-Cambrian

The story of a name

When BMC decided to market the A55 Cambridge in North America, the company was afraid it would run afoul of Canadian copyright laws with the word "Cambridge." So the substitute name "Cambrian" was agreed on. After CAR LIFE's story went to press, however, BMC's lawyers advised the company that "Cambridge" was safe to use after all. The car is now the A55 Cambridge in the U.S. as well as in England. Our apologies to our readers.